Afghanistan correspondent

“I just want someone to hear my voice. I’m in pain, and I’m not the only one,” an Afghan university student tells us, blinking back tears.

“Most of the girls in my class have had suicidal thoughts. We are all suffering from depression and anxiety. We have no hope.”

The young woman, in her early twenties, tried to end her own life four months ago, after female students were barred from attending university by the Taliban government in December last year. She is now being treated by a psychologist.

Her words offer an insight into a less visible yet urgent health crisis facing Afghanistan.

“We have a pandemic of suicidal thoughts in Afghanistan. The situation is the worst ever, and the world rarely thinks or talks about it,” says psychologist Dr Amal.

“When you read the news, you read about the hunger crisis, but no-one talks about mental health. It’s like people are being slowly poisoned. Day by day, they’re losing hope.”

Note: The BBC has changed or withheld the names of all interviewees in this piece, to protect them.

Dr Amal tells us she received 170 calls for help within two days of the announcement that women would be banned from universities. Now she gets roughly seven to 10 new calls for help every day. Most of her patients are girls and young women.

In Afghanistan’s deeply patriarchal society, one worn out by four decades of war, the UN estimates that one in two people – most of them women – suffered from psychological distress even before the Taliban takeover in 2021. But experts have told the BBC that things are now worse than ever before because of the Taliban government’s clampdown on women’s freedoms, and the economic crisis in the country.

It’s extremely hard to get people to talk about suicide, but six families have agreed to tell us their stories.

Nadir is one of them. He tells us his daughter took her own life on the first day of the new school term in March this year.

“Until that day, she had believed that schools would eventually reopen for girls. She had been sure of it. But when that didn’t happen, she couldn’t cope and took her own life,” he says. “She loved school. She was smart, thoughtful and wanted to study and serve our country. When they closed schools, she became extremely distressed and would cry a lot.”

It is evident that Nadir is in pain as he speaks.

“Our life has been destroyed. Nothing means anything to me anymore. I’m at the lowest I’ve ever been. My wife is very disturbed. She can’t bear to be in our home where our daughter died.”

We have connected his family and others quoted in this piece to a mental health professional.

The father of a woman in her early twenties told us what he believes was the reason behind his daughter’s suicide.

“She wanted to become a doctor. When schools were closed, she was distressed and upset,” he says.

“But it was after she wasn’t allowed to sit for the university entrance exam, that’s when she lost all hope. It’s an unbearable loss,” he adds, then pauses abruptly and begins to cry.

The other stories we hear are similar – girls and young women unable to cope with their lives, and futures coming to a grinding halt.

We speak to a teacher, Meher, who tells us she has tried to take her own life twice.

“The Taliban closed universities for women, so I lost my job. I used to be the breadwinner of my family. And now I can’t bear the expenses. That really affected me,” she says. “Because I was forced to stay at home, I was being pressured to get married. All the plans I had for my future were shattered. I felt totally disoriented, with no goals or hope, and that’s why I tried to end my life.”

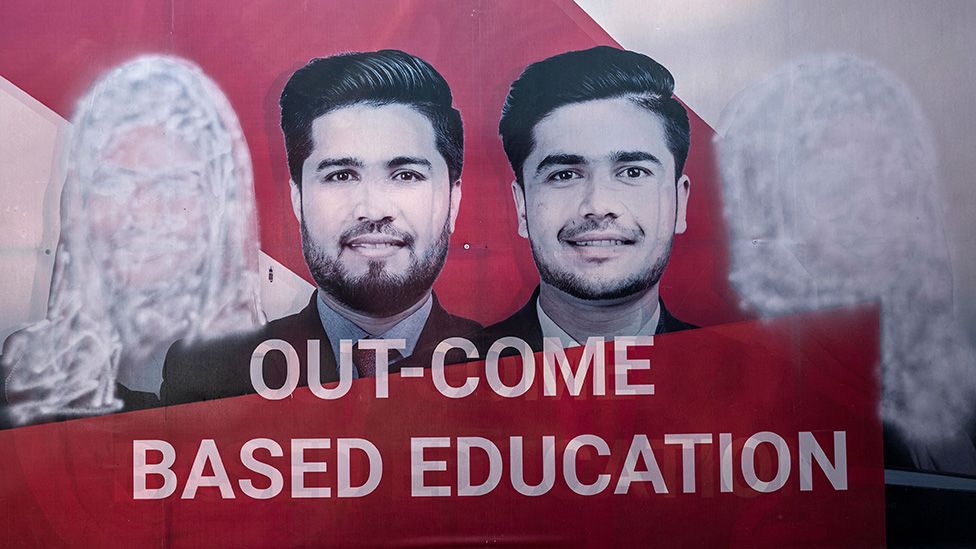

We started looking into this crisis because we saw multiple articles in local news portals reporting suicides from different parts of the country.

“The situation is catastrophic and critical. But we are not allowed to record or access suicide statistics. I can definitely say though that you can barely find someone who is not suffering from a mental illness,” says Dr Shaan, a psychiatrist who works at a public hospital in Afghanistan.

A study done in Herat province by the Afghanistan Centre for Epidemiological Studies, released in March this year, has shown that two-thirds of Afghan adolescents reported symptoms of depression. The UN has raised an alarm over “widespread mental health issues and escalating accounts of suicides”.

The Taliban say they are not recording suicide numbers, and they didn’t respond to questions about a surge in figures. Because of the stigma attached to it, many families do not report a suicide.

In the absence of data, we’ve tried to assess the scale of the crisis through conversations with dozens of people.

“Staying at home without an education or a future, it makes me feels ridiculous. I feel exhausted and indifferent to everything. It’s like nothing matters anymore,” a teenage girl tells us, tears rolling down her face.

She attempted to take her own life. We meet her in the presence of her doctor, and her mother, who doesn’t let her daughter out of her sight.

We ask them why they want to speak to us.

“Nothing worse than this can happen, that’s why I’m speaking out,” the girl says. “And I thought maybe if I speak out, something will change. If the Taliban are going to stay in power, then I think they should be officially recognised. If that happens, I believe they would reopen schools.”

Psychologist Dr Amal says that while women have been hit harder, men are also affected.

“In Afghanistan, as a man, you are brought up to believe that you should be powerful,” she says. “But right now Afghan men can’t raise their voice. They can’t provide financially for their families. It really affects them.

“And unfortunately, when men have suicidal thoughts, they are more likely to succeed in their attempts than women because of how they plan them.”

In such an environment, we ask, what advice does she give her patients?

“The best way of helping others or yourself is not isolating yourself. You can go and talk to your friends, go and see your neighbours, form a support team for yourself, for instance your mother, father, siblings or friends,” she says.

“I ask them who’s your role model. For instance, if Nelson Mandela is someone you look up to, he spent 26 years in jail, but because of his values, he survived and did something for people. So that’s how I try to give them hope and resilience.”

Source: BBC